Night-time light pollution harms the environment but simple changes can reduce impact, report concludes

Science communicators at the University of the West of England (UWE Bristol) have produced a detailed report that highlights how to stop or lower environmental harm caused by light pollution at night. The report concludes that the impact of light pollution can be lowered through a variety of measures, including: national legislation, such as artificial light free zones; practical schemes in towns and villages, such as sensor triggered lights; technical adaptations to lighting design, for example, to limit light spill; and identifying sensitive taxa or habitats, then managing these areas to avoid the impact, i.e. removing lighting, or using red lights rather than white.

The growing world population coupled with industrialisation has led to an increase in use of artificial light at night globally, with light pollution a rapidly emerging threat. In Europe for example, the loss of truly dark spaces was five per cent in just six years from 2015 to 2021. The report, written by the Science for Environment Policy team, at the university’s Science Communication Unit for the European Commission, illustrates that despite human kind’s need for night-time lighting, light pollution is causing a severe problem for the environment and human kind, disrupting wildlife behaviour and migration patterns, and impacting human health.

Nicola Shale, an ecologist and the editor of the report, said: “It’s important to dispel the myth that an area with brighter light at night is always safer. We have all experienced the blindness caused by poorly designed glaring light at night, it temporarily blinds you and makes it difficult to see your surroundings easily. Dimmer lighting located on suburban paths and through parks can benefit biodiversity and our (human) health.”

Night time active species including migratory birds, the European glow worm and rare lesser horseshoe bat are just some of the array of light sensitive species that can be detrimentally affected by light pollution from electrical lighting at night. This light can come from outdoor lighting on streets, at ports, or light spilling out from buildings (such as stadiums or skyscrapers) and ships.

The report used European and global case studies of best practice to highlight the types of good practise that can be used in a variety of settings. One example is the National 9/11 Museum's ‘Tribute in Light’, which releases trapped migratory birds by the intermittent switching off of the light. Dimming lighting, part night lighting and sensor activated lighting is also recommended best practice to protect light sensitive species and save on energy consumption. Other measures suggested in the report include: adaptive street lighting, buffer zones around dark reserves, dark corridors – connecting dark infrastructure, buildings designed to reduce light spill and reflection on glass, and dense vegetation to hinder light spill.

Nicky Shale said: “The ideal solution is to remove or switch off artificial lights at night, keeping naturally dark areas dark and protecting species in these habitats. But when there is a human need and this isn’t feasible, the least amount of light should be used, with precise lighting only of the area needed and only for the time needed. Warmer coloured LED lights (amber and red) are less harmful to most species, than white or blue lights. These are another option to mitigate the impacts from light pollution.”

Associate Professor Mark Steer, a member of the Ecology and Conservation Research Lab at UWE Bristol, said: “This is an important piece of work that underscores the urgent measures needed to mitigate the growing environmental harm caused by light pollution. Turning off lights in natural areas, and removing them where possible, should always be the default, but reducing harm by using dimmable, sensor controlled and shielded lights is preferable where lighting is a necessity.

“Red lights do seem to have a lower impact on many species compared to white light, but this is not always the case. The lesser horseshoe bat is so light sensitive even red light affects their behaviour. The report helps to provide some of the solutions needed to mitigate the impacts of new development, as well as offering hope for restoring populations of light-sensitive species where they currently cannot survive.”

The full report can be found on the European Commission website.

Related news

27 January 2026

From scraps to soil: the UWE Bristol alum transforming campus food waste into fertile compost to feed university garden

A UWE Bristol alum has gone back to his roots to transform food waste from his former university into living, nutrient-rich compost to feed back into its student and staff-run Community Garden.

20 January 2026

UWE Bristol becomes South West Regional Hub lead for national Climate Ambassadors scheme

UWE Bristol is the new regional hub lead for the Climate Ambassadors scheme, a national initiative helping to drive the development of climate action plans in education settings across England.

15 December 2025

UWE Bristol rises eleven places in People & Planet University League

UWE Bristol has risen to 14th in the People & Planet University League (UK), a jump of eleven places.

12 December 2025

UWE Bristol’s environmentally conscious and student-focused accommodation wins three awards

Purdown View, the world's largest certified Passivhaus student accommodation development, has been recognised at Property Week Student Accommodation Awards.

20 November 2025

UWE Bristol ranked among top 12 per cent of universities globally for sustainability

UWE Bristol has climbed over 400 places in the QS World University Sustainability Rankings 2026, which evaluates universities on a range of environmental and social impacts.

06 November 2025

UWE Bristol welcomes West of England Mayor for annual Green Week

Helen Godwin, Mayor of the West of England, visited UWE Bristol during its annual Green Week to see the sustainability-driven research, innovation and skills initiatives that are helping to power the growth of the region’s green economy.

16 October 2025

UWE Bristol signs Repair and Reuse Declaration in commitment to sustainable initiatives

UWE Bristol is the first UK university to sign the Repair and Reuse Declaration as a whole institution, a call to legislators and decision makers to tackle climate change through greater repair and reuse support.

15 October 2025

UK food needs radical transformation on scale not seen since Second World War, new report finds

A new report from the Agri-Food for Net Zero Network+ finds urgent action on food is needed if the UK is to reboot its flagging economy, save the NHS billions, ensure national food security, and meet climate commitments.

24 September 2025

UWE Bristol to help protect threatened forest in Madagascar in £800k project

UWE Bristol is a partner in a groundbreaking project awarded almost £800,000 in funding to protect one of Madagascar’s most precious and threatened forests.

24 February 2025

WESTbusStop+ makes sustainable travel more convenient

A new WESTbusStop+ bringing together buses and other ways to travel has been officially opened at UWE Bristol’s Frenchay campus.

03 January 2025

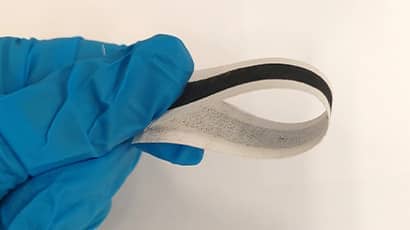

Big leap forward for environmentally friendly ‘e-textiles’ technology

Research led by UWE Bristol and the University of Southampton has shown wearable electronic textiles (e-textiles) can be both sustainable and biodegradable.

28 November 2024

Work of UWE Bristol academics features in Government report on air quality measurement

Two UWE Bristol academics have made contributions to an influential Government report on the measurement of air pollution.

You may also be interested in

Media enquiries

Enquiries related to news releases and press and contacts for the media team.

Find an expert

Media contacts are invited to check out the vast range of subjects where UWE Bristol can offer up expert commentary.

Science Communication Unit (SCU)

The SCU is internationally renowned for its diverse and innovative activities, designed to engage the public with science.

We're creating tomorrow, today. RISE

Collaborating with industry, public sector bodies and communities, we’re redefining horizons and challenging conventions to impact lives positively.